Winner’s Bag

Aldrich Potgieter’s clubs: Inside his Rocket Classic-winning setup

Aldrich Potgieter claimed his first Tour title at the Rocket Classic after making a few key changes to his Titleist golf ball and iron setup.Aldrich Potgieter’s clubs: Inside his Rocket Classic-winning setup

Aldrich Potgieter claimed his first Tour title at the Rocket Classic after making a few key changes to his Titleist golf ball and iron setup.Patrick Reed’s clubs: Inside his LIV Dallas-winning setup

Patrick Reed outlasted everyone at LIV Dallas to secure his first win on the breakaway circuit. Take a look at his unique bag setup here.Keegan Bradley’s clubs: Inside his Travelers-Winning setup

Keegan Bradley earned PGA Tour victory No. 8 at the Travelers Championship. Take a look at his golf bag setup here.Minjee Lee’s clubs: Inside her KPMG Women’s PGA-winning setup

MinJee Lee trusted a bag full of Callaway gear to secure Major Win No. 3 this week in Frisco, Texas at the KPMG Women’s PGA Championship.J.J. Spaun’s clubs: Inside his U.S. Open-winning setup

J.J. Spaun won the U.S. Open at Oakmont, becoming the first player to win a major with a zero torque putter. Here is his full gear setup.Ryan Fox’s clubs: Inside his RBC Canadian Open winning-setup

Ryan Fox earned his second career win at the RBC Canadian Open. Here is the full bag of Cleveland/Srixon and Ping gear he used to win it.Joaquin Niemann’s clubs: Inside his LIV Virginia-winning setup

Joaquin Niemann got his fourth win of the season at LIV Golf Virginia. Here is the full bag of Ping golf clubs he used in the win.How a Tour pro sets up their bag for playing overseas | Fully Equipped

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Full Equipped, Max Greyserman explains what he does to his bag for links golf.How Max Greyserman became a certified golf gear nerd | Fully Equipped

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Fully Equipped, Max Greyserman explained to Johnny Wunder how his gearhead journey began.Can L.A.B. Golf’s success be replicated in the driver market? | Fully Equipped

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Fully Equipped, Johnny Wunder explains why it’s hard for a smaller company to break in to the driver market.Why getting fit for your golf shafts is essential | Fully Equipped

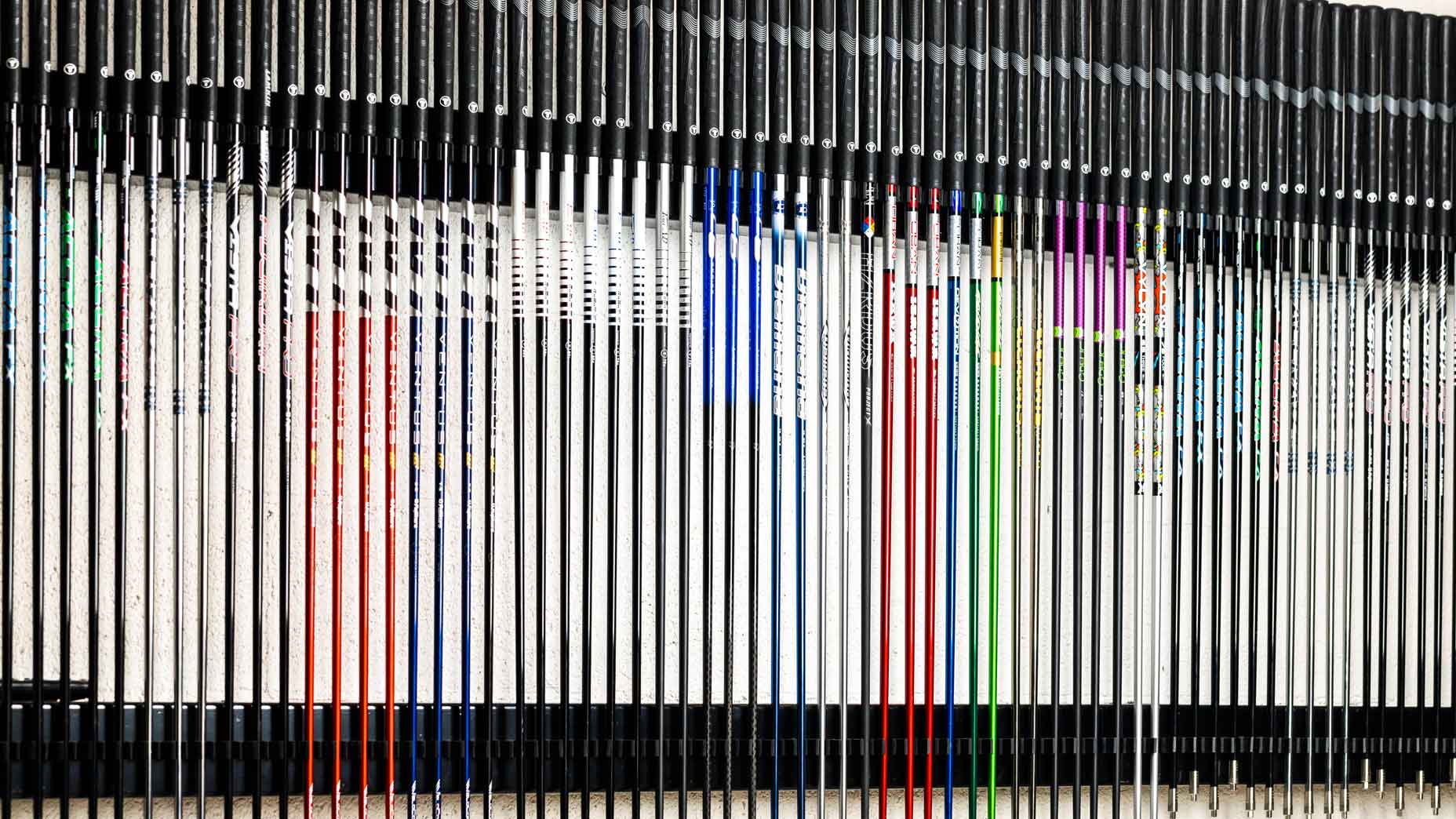

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Fully Equipped, our gear experts explain why it’s essential that golfers test and get fit for their shafts.Why this part of iron design is more of a focus than ever | Fully Equipped

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Fully Equipped, Kris McCormack discusses why you’re hearing more about this part of iron design.Here’s how wet conditions can impact your golf ball | Fully Equipped

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Fully Equipped, Kris and Jack discuss what the conditions Sunday at Oakmont can do to a golf ball.What Bettinardi’s father-son operation means to them | Fully Equipped

On this week’s episode of GOLF’s Fully Equipped, Bob and Sam Bettinardi explain what their father-son operation means to them.The key role Lydia Ko’s Ping driver played in her gold medal performance

Lydia Ko’s equipment setup helped her win gold on Saturday in France. The gear included a G430 Max 10K driver that played a supporting role.How this ‘no-brainer’ Xander Schauffele gear swap gave him more control

The Open champion made several equipment changes at the start of the season, but one took his game to new heights.This gear constant has propelled Scottie Scheffler to new heights

Scheffler’s putter garners most of the attention, but that doesn’t mean the driver deserves to play second fiddle.Titleist’s GT drivers already have pros raving about 1 crucial aspect

An early Tour launch allowed pros to test Titleist’s GT driver at the Memorial. Many are raving about one performance improvement.What happens when pros use a persimmon driver? | Wall-to-Wall

The latest edition of GOLF’s weekly equipment notes takes a look at Justin Rose’s red-hot putter, Tour prototypes, persimmon woods and more.Xander Schauffele’s multi-colored putter has special significance

The latest edition of GOLF’s weekly equipment notes takes a look at the putter Schauffele used to win his first major championship.How Justin Thomas gained almost 10 yards with 1 driver change

The drive to peak for the PGA Championship saw Thomas make a change to a driver that’s already paying dividends.We put Nikon’s latest rangefinder to the test | Proving Ground

Nikon’s Coolshot Pro II Stabilized rangefinder has plenty of bells and whistles. The latest Proving Ground analyzes the benefits.How good are Mizuno’s JPX925 Hot Metal irons? We found out | Proving Ground

Mizuno’s JPX Hot Metal lineup lived up to the hype — and then some — in the latest Proving Ground head-to-head test.Is Titleist’s GT driver worth the fanfare? We put it to the test | Proving Ground

For years, I’ve worried about the “big miss” with the driver. Titleist’s GT3 helped change my way of thinking on the tee box.How XXIO’s lightweight clubs make golf so much easier | Proving Ground

XXIO offers premium lightweight clubs to help moderate swing speed golfers gain control and distance, and we put them to the test.Are Cobra’s Limit3d irons worth the $3K price tag? | Proving Ground

The latest edition of GOLF’s Proving Ground pits Cobra’s Limit3d against the writer’s gamer iron set to see if they live up to the hype.I tried it: These user-friendly wedges make short-game shots much easier

We tested Cleveland’s Smart Sole Full-Face wedges to find out if they make club selection around the greens easier.Does this red-hot putter live up to the hype? | Proving Ground

The recent increase in L.A.B. Golf usage on Tour led GOLF’s Jonathan Wall to wonder if the putter could live up to the hype.Cobra’s 3D-printed irons pair blade look with game-improvement forgiveness

We tested Cobra’s 3DP Tour irons. Here’s why they’re a unique offering, and who should consider adding them to their bags.ClubTest 2025 testing process: How we identified the year’s best clubs

For GOLF’s 2025 ClubTest, we brought back thorough player testing to produce a firsthand look at how the latest clubs really perform.Best drivers | ClubTest 2025

For ClubTest 2025, we put all the newest driver models to the test to determine the best drivers for every type of golfer. Here are the results.Best irons | ClubTest 2025

Looking for the best new irons? We have you covered. As part of ClubTest 2025, we reviewed and organized the top irons into five categories.Best fairway woods | ClubTest 2025

If you’re in search of the best fairway woods, look no further. Here are the top fairway woods in four categories from ClubTest 2025.Best hybrids | ClubTest 2025

For ClubTest 2025, we reviewed and tested the best hybrids for the new year to help you find the right one for your game.Best drivers for forgiveness | ClubTest 2025

When it comes to the best drivers for forgiveness, these nine new models stand out. Learn all about them with our ClubTest 2025 reviews.

Join InsideGOLF today!

GOLF.com’s membership program is one of the game’s best values. For only $39.99/year, you’ll get access to exclusive content and also a host of discounts and promotions, including…

- Dozen Srixon Z-STAR XV Golf Balls (+$45 retail value)

- $20 Instant Credit at Fairway Jockey

- One Year (8 issues) of Golf Magazine (+$79 Newsstand value) – U.S. members Only

- +600 Issue Golf Magazine Digital Archive (1959-Present)

- Bucket-List golf trips and experiences

- FREE True Spec Fitting wtih any club purchase

- $100 OFF qualified purchases at Miura and Fairway Jockey

- 50% OFF new Golf Logix App/membership

- Plus so much more!