Pros Teaching Joes w/ Zephyr Melton

Bubba Watson taught me how to hit crazy hooks and slices

Is Bubba Watson the best shot-shaper in golf? He shares his tricks for working the ball and tries helping us moving it both ways.Lexi Thompson taught me how to hit a punch shot into the wind

On the latest edition of Pros Teaching Joes, LPGA star Lexi Thompson explains how to hit a low shot into the wind.Maria Fassi explains each step of her green-reading strategy

At a recent tournament, LPGA pro Maria Fassi explained her green-reading process and how she approaches each putt she faces.The secret to escaping a fried egg lie, according to an LPGA pro

In this edition of Pros Teaching Joes, LPGA pro Brittany Lang shares the secrets for escaping a fried egg lie in the bunker.Pros Teaching Joes: Marina Alex shares the keys to reading Bermuda greens

Two-time LPGA champ Marina Alex knows a thing or two about putting on Bermuda greens, so I enlisted her advice on reading them effectively.3 keys for hitting off a downhill lie, according to a Masters champion

On this edition of Pros Teaching Joes, 2008 Masters winner Trevor Immelman shares the keys to hitting off a downhill lie.3 tips to improve your short putts from an LPGA pro

In this edition of Pros Teaching Joes, LPGA pro Angel Yin gives three tips that will help improve your short-range putting.Bombers use this key move with their feet to hit long drives

In today’s edition of Play Smart, Dr. Greg Rose explains a key move that the longest players in the world use to hit bombs off the tee.Why trashing this key piece of information can lead to lower scores

In today’s edition of Play Smart, former PGA Tour pro Colt Knost explains why you should ignore the pin sheet.Fried-egg lie? Hitting the hosel can bail you out (seriously!)

In today’s edition of Play Smart, instructor Kelan McDonagh explains why hitting the hosel could help with fried-egg bunker shots.The ‘simple’ mental trick Padraig Harrington uses to perform under pressure

In this edition of Play Smart, we break down Padraig Harrington’s mantra that helps him deliver under pressure.Why this golf-swing cliche is actually terrific advice

In today’s edition of Play Smart, GOLF Top 100 Teacher Tony Ruggiero breaks down the merits of some common swing advice.Should you use a weak grip or a strong grip? Top teacher explains

In this edition of Play Smart, GOLF Teacher to Watch Christy Longfield explains the differences in weak grips and strong grips.Rory McIlroy reveals ‘most effective way’ to shoot lower scores

In this edition of Play Smart, we hear from Rory McIlroy on the most effective way for amateurs to shoot lower scores.Find the center of your stance for better contact with your irons

Finding the true center of your stance will help you hit better shots with your irons. GOLF Top 100 Teacher Joe Plecker shows you how.6 shots amateurs never practice — but they should

There are a number of shots that amateur golfers never practice. Here are six from Top 100 Teacher Tom Stickney that will help your game.This common mistake kills your bunker game. Here’s how to fix it

Having trouble escaping the sand? You might be hitting too far behind the ball in the bunker. Here’s how to fix that flaw.How high-tech mobility analysis diagnosed this golfer’s swing flaws

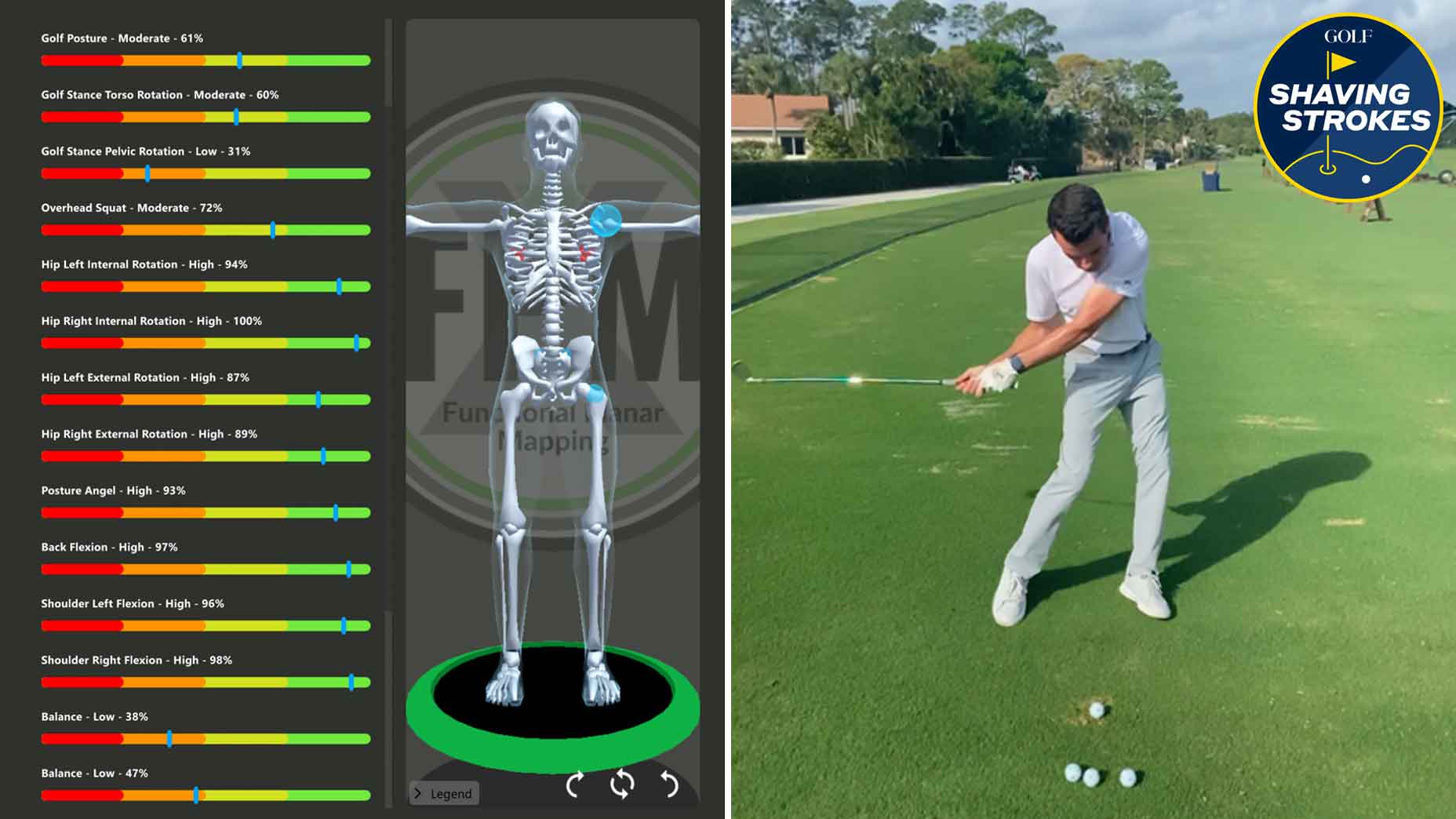

In this edition of Shaving Strokes, Top 100 Teacher Tom Stickney explains how he used Proscreen AI to help diagnose a student’s flaws.This sneaky ‘toe tap’ move will improve your chipping instantly

Want to boost your short game? This simple drill will teach you to properly shift your pressure on delicate wedge shots around the green.Simple course-management tips for breaking 100, 90, 80 and par

Want to break through a scoring barrier this season? Follow these simple tips from GOLF Top 100 Teacher Joey Wuertemberger.Want to hit longer drives? Use this drill to increase your attack angle

Hitting longer drives can be achieved by increasing your attack angle. Here’s an easy drill to practice that.

Join InsideGOLF today!

GOLF.com’s membership program is one of the game’s best values. For only $39.99/year, you’ll get access to exclusive content and also a host of discounts and promotions, including…

- Dozen Srixon Z-STAR XV Golf Balls (+$45 retail value)

- $20 Instant Credit at Fairway Jockey

- One Year (8 issues) of Golf Magazine (+$79 Newsstand value) – U.S. members Only

- +600 Issue Golf Magazine Digital Archive (1959-Present)

- Bucket-List golf trips and experiences

- FREE True Spec Fitting wtih any club purchase

- $100 OFF qualified purchases at Miura and Fairway Jockey

- 50% OFF new Golf Logix App/membership

- Plus so much more!